It’s Not Too Late to Roll Back MCP

.png)

2025 was dubbed the Year of AI Agents, so why aren’t agents buying cars yet?

Agents still aren’t very good at making hard decisions.

Humans make a ton of decisions. To the tune of 35,000 a day. Some are trivial and some are huge, but they’re constantly being made.

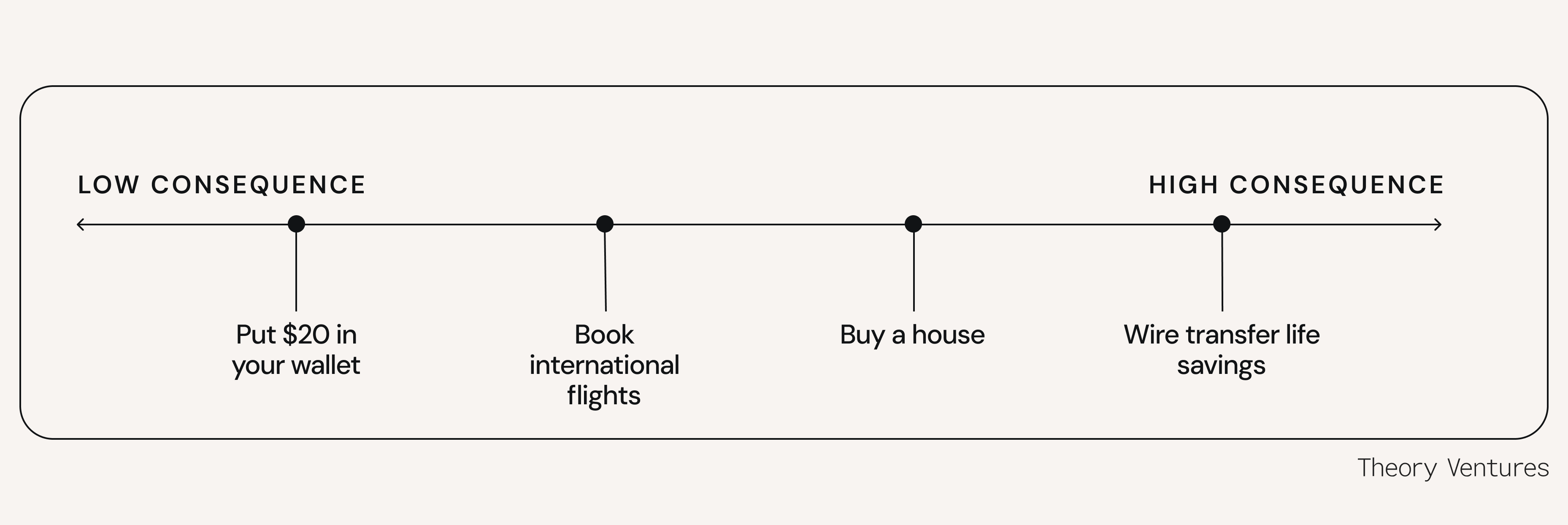

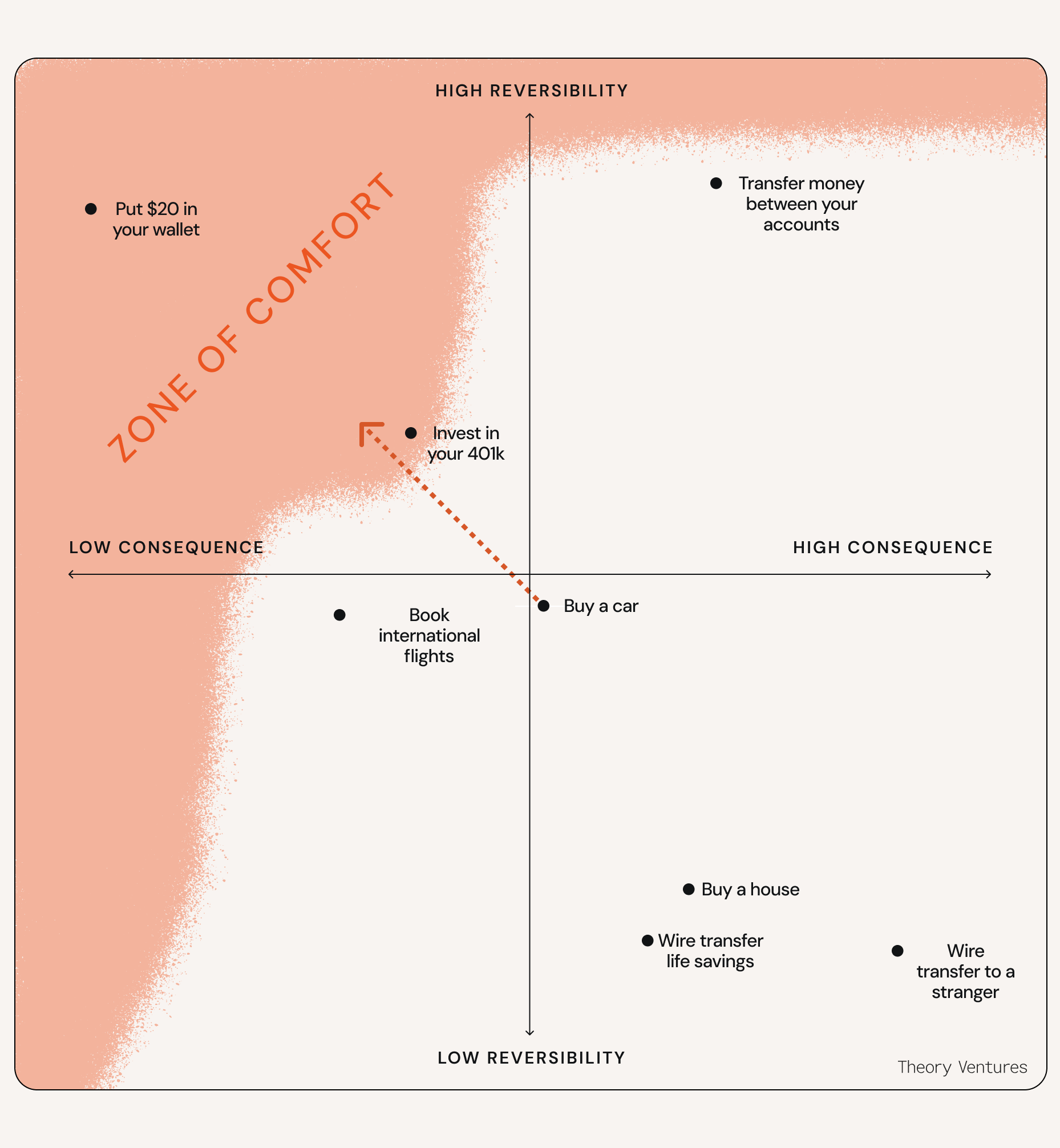

Every decision exists on a spectrum from low consequence to high consequence. Decisions that are obviously verifiable or very small have pretty low consequences.

The farther you go from low consequence to high consequence, the more verification you need to do to make that decision. Putting $20 in your wallet is a trivial decision, so the consequences are low. Conversely, the consequences of wire transferring your life savings are huge, so you need to verify every minute detail.

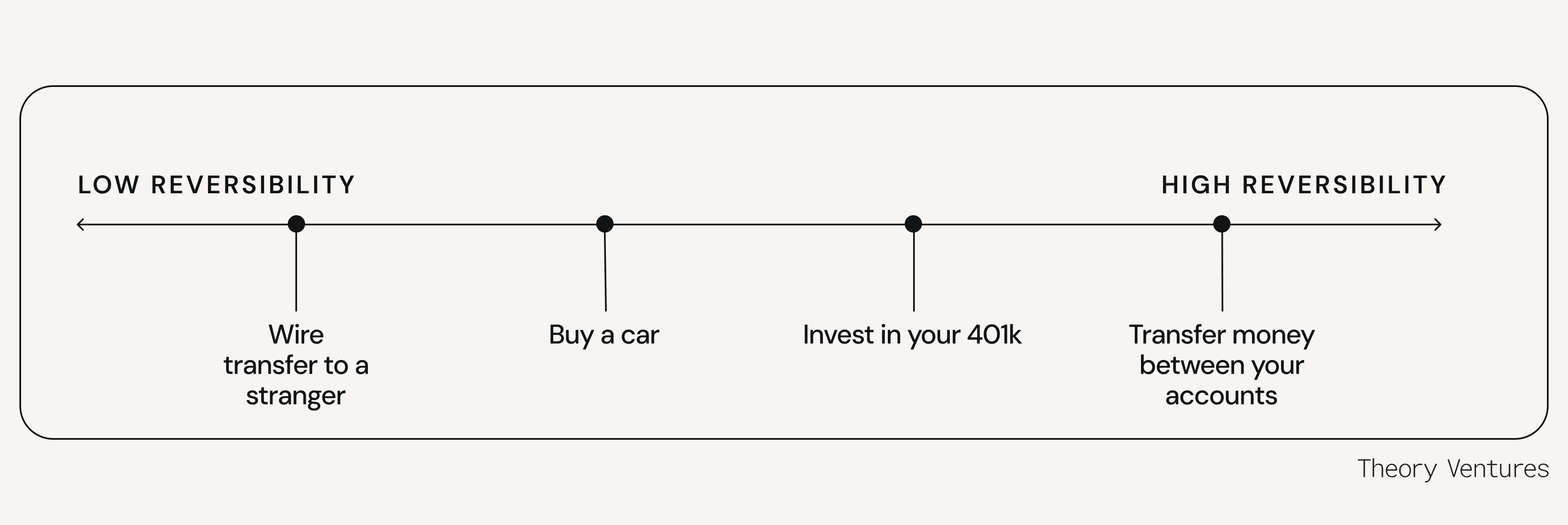

Another way to classify decisions is on a spectrum from high reversibility to low reversibility. Transferring funds between your own bank accounts is easily reversible, while burning a dollar is impossible to reverse.

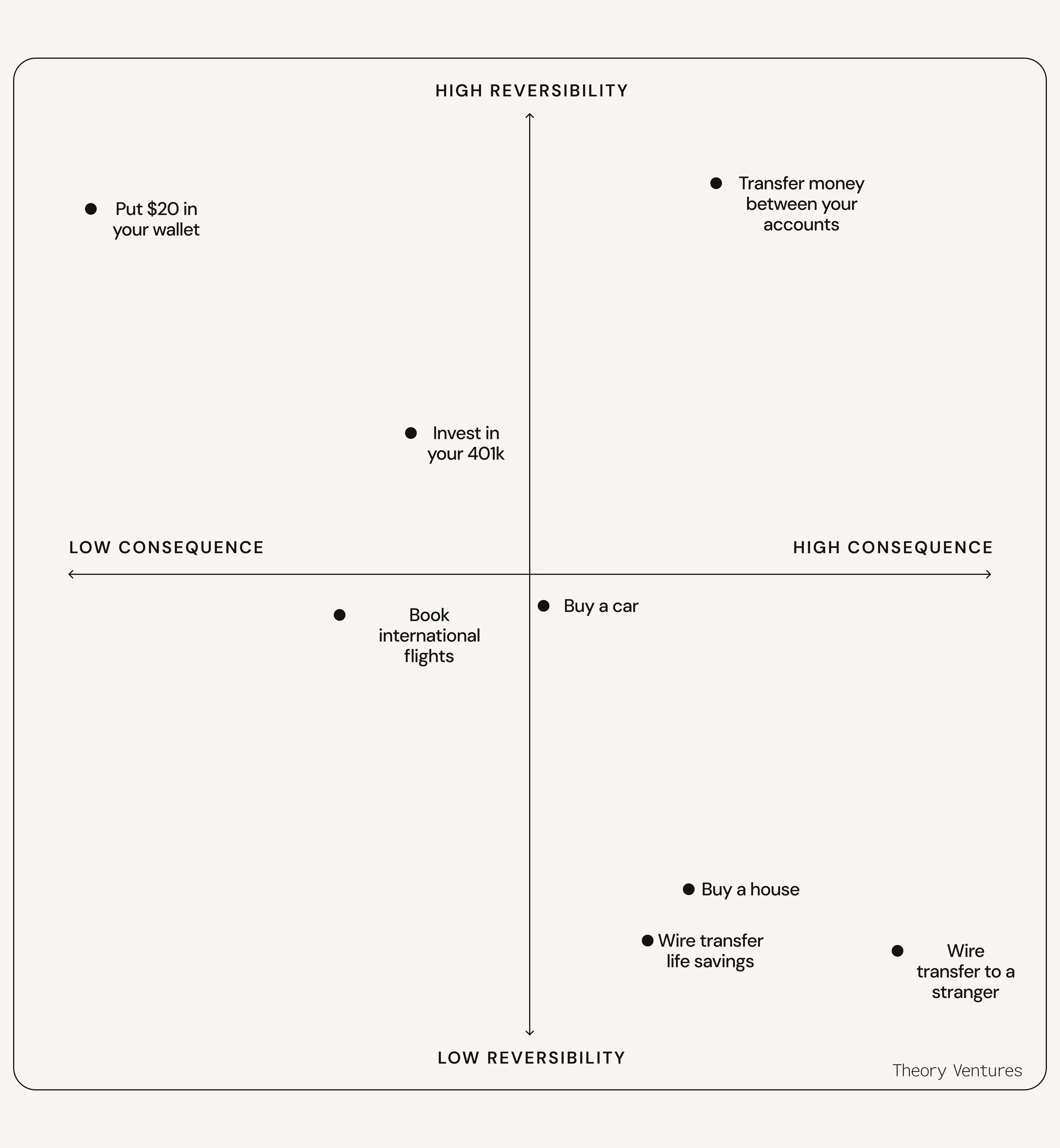

Of course, reversibility and consequence don’t exist detached from each other.

Decisions like “transfer money between your accounts” have high reversibility but also high consequences – while you can undo the decision, you need to feel really confident you’re transferring money to the right account, because the consequences are significant if you accidentally transfer it to someone else’s account.

Some decisions, like wiring your life savings, are both high consequence and low reversibility. It’s impossible to undo this decision and if you get it wrong, the consequences are incredibly high.

The farther right and farther down you go in this consequence matrix, the “harder” a decision is to make because the consequences of getting it wrong are high and you’re less able to reverse it.

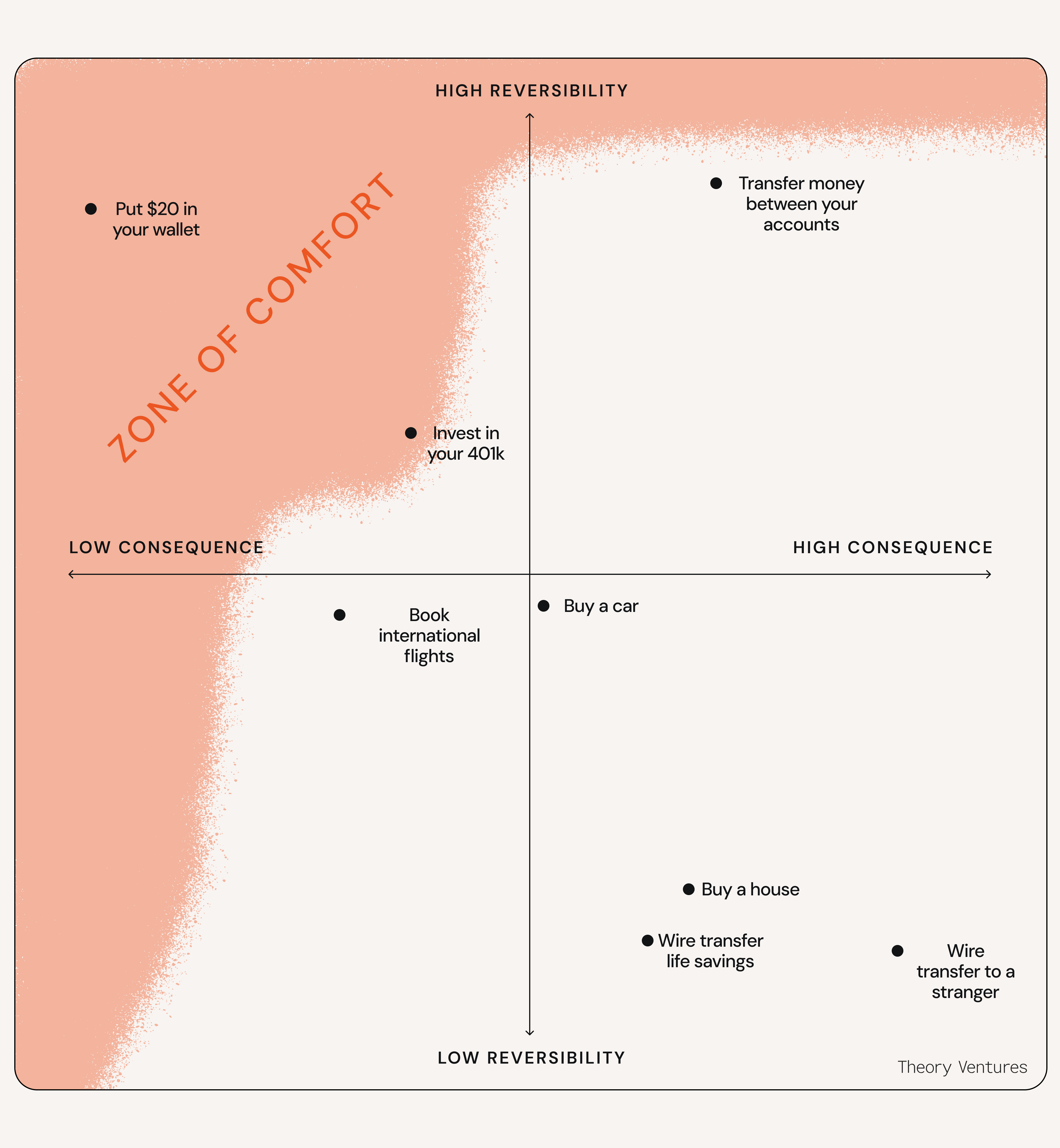

I’m really only comfortable making decisions near the top left quadrant. Everyone has a different zone of comfort with making decisions, but mine looks like this:

The harder decisions end up getting made eventually, of course. But only because I’ve done work to move them up and to the left into my zone of comfort. Take buying a car:

- Buying from a dealership that has a generous return policy makes the decision more reversible.

- Researching reliability ratings of cars makes the decision have lower consequences. I know buying this car isn’t going to lead to big maintenance issues down the road.

Stack up enough of these and the decision makes it into my zone of comfort.

As you can tell, the farther down/right a decision is, the more I need to do to move it into my zone of comfort.

This is especially pronounced if a decision is irreversible, a.k.a. a one-way-door (OWD). For OWDs, like wiring money, there’s no way to make it more reversible. The only way to make OWD decisions comfortable is huge amounts of verification to lower the consequences. If I’m wire transferring my life savings, no amount of verification is too much; I’m verifying the receivers credentials, using a trustworthy bank, quadruple checking the account numbers, etc.

Tool calling has exploded onto the scene in 2025, giving agents a standardized protocol to make requests to other systems. Carvana could surely build a tool that lets your agent purchase a car.

The reason agents aren’t buying cars yet is tool calling only makes it possible for agents to make decisions. It does nothing to move that decision into the “zone of comfort”. When an agent is using tools outside its system boundary to make decisions (e.g. Claude uses Carvana’s tool to buy a car) there’s nothing that makes that decision more reversible. There’s nothing that lowers the consequences.

Frontier labs would have us believe the answer is smarter models, more parameters, or bigger training budgets.Sadly, they’re wrong.

AGI isn’t enough.

Fortunately, we can find the answer to why agents aren’t buying cars yet where agents are having their biggest impact: Software Development.

The reason agents are making real decisions in software development and aren’t buying cars is because software development is made up entirely of systems that make decisions more reversible and less consequential.

Technologists have spent decades building systems that do this at every step of development:

- Git lets developers undo code changes.

- Code review lets us verify each other’s code is ready to deploy.

- Database transactions let us verify our database queries succeed before committing them.

- Observability platforms let us spot issues and fix them before they get worse.

Agents get to use these already existing systems and since we know how to monitor and use them, we feel good about letting agents make real software decisions (some people do, at least).

For agents to make “hard” decisions in domains outside of software development, they need systems that make their decisions more reversible and less consequential.

Like software development, the suite of systems that needs to exist is huge but almost none of it exists today.

Making Agent Decisions Less Consequential

Making a decision less consequential is all about knowing and signing off on the outcomes of making that decision. It’s unlikely you will ever get rid of outcomes or guarantee a given outcome, but knowing the possibilities gives you information that makes the decision less consequential.

If you buy a house without doing any inspections and find out after you move in that it needs a new foundation, that’s a bad outcome.

Alternatively, if you get an inspection done before buying it and learn it has foundation cracks, you get to make an informed decision. This makes the decision less consequential.

Because you know the likely outcome (your house needs a new foundation), you can decide if that’s acceptable. Maybe:

- You own a construction company so it’s not a big deal.

- You can use that information to negotiate a lower price.

- You love the house so much that any amount of repairs are fine.

Letting an agent buy a house means it has to know all that context and nuance as it’s making decisions. And you have to trust it’ll interpret and act on it as expected.

It needs to know your skills are aligned with the type of repairs this house might need.

It needs to know the repairs are more costly than you’re comfortable with.

It needs to know how much you love the house.

Ensuring agents know about and can act on behalf of your hopes and dreams is an alignment problem. Major AI labs and research organizations are focused on solving this problem, so while it’s important, I want to focus on something more tractable given my engineering background: making agent decisions more reversible.

Making Agent Decisions More Reversible

The AI industry has introduced some systems to make decisions more reversible, but they aren’t yet sufficient. Snapshots are the most popular system for reversing decisions.

If an agent is working within a single system, that system can keep snapshots of state at checkpoints along the way. It makes it straightforward to reverse decisions. If the agent or human needs to reverse a decision, all they need to do is reset the system state to whatever it was at the last checkpoint.

.png)

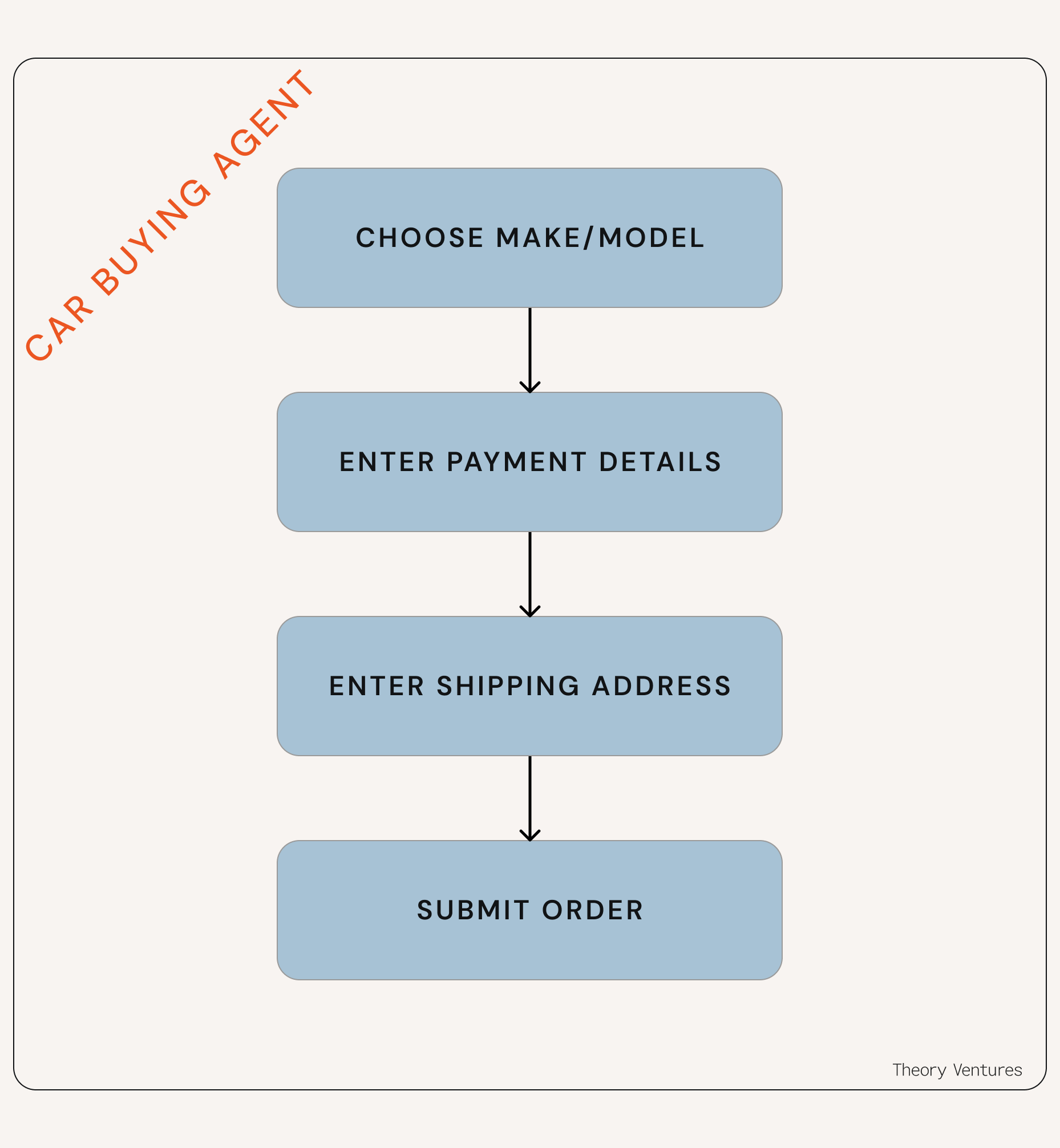

Again, take buying a car for example. A Carvana agent would need to:

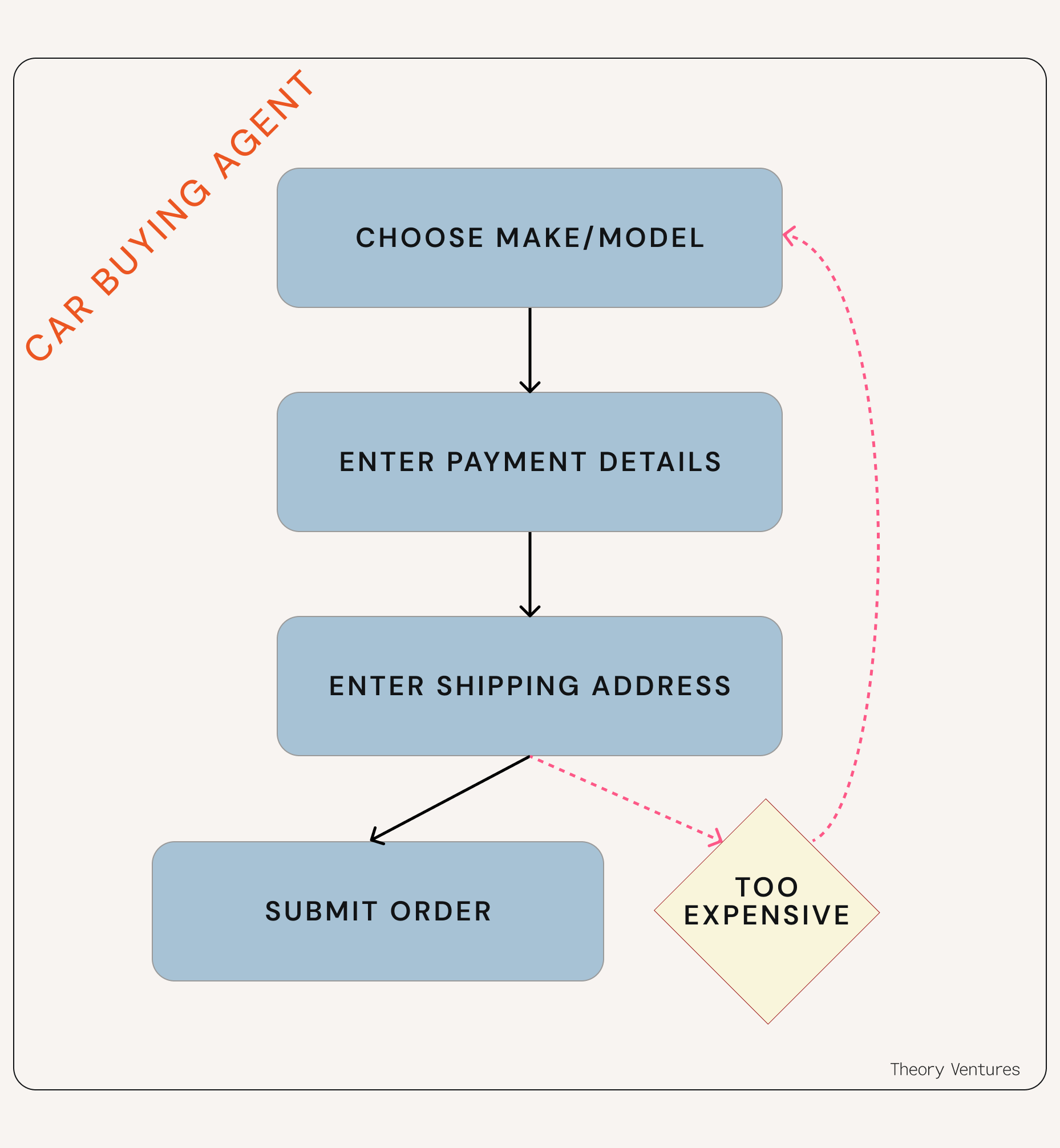

Carvana takes snapshots at every step of this workflow so decisions can be reversed if needed. Imagine an agent entering your shipping address, then seeing that shipping prices put the car out of the budget you gave it, and realizing it needs to go back and choose a cheaper make or model. Snapshots let the agent reverse.

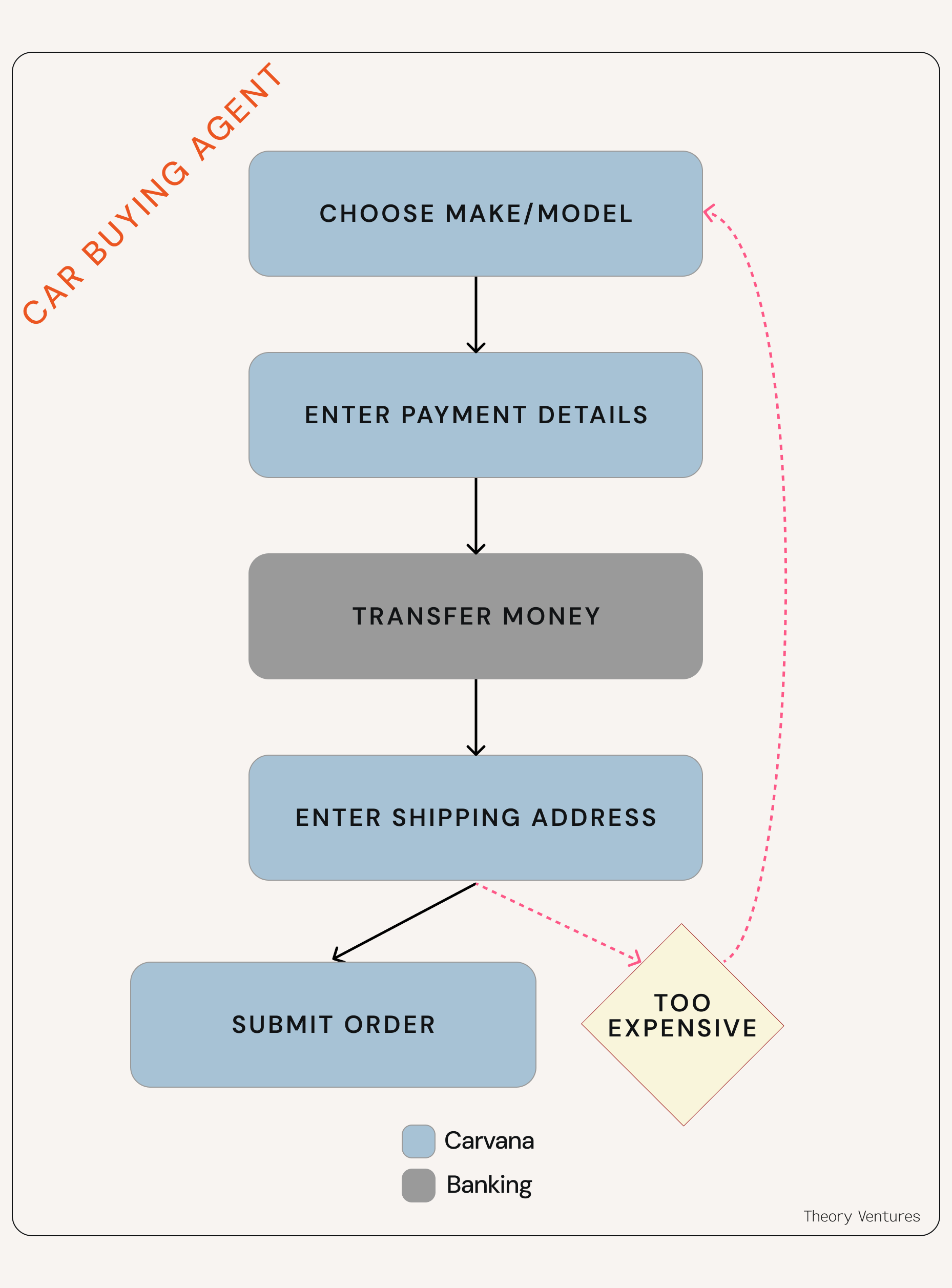

Part of the reason buying a car is hard is there are lots of decisions to make. An agent buying a car might also need to transfer money to the right bank account so it can make the downpayment.

The banking infrastructure lives outside of Carvana’s architecture, so the agent needs a tool to make the transfer. It’s not possible for the agent to complete this task without it. This is why MCP, or Model Context Protocol, is so exciting!

The trouble is, as soon as you add tool calling to the banking infrastructure to Carvana’s agent, snapshots don’t make the car buying workflow reversible anymore. If the Carvana agent transfers money via a tool and later discovers the car’s too expensive, there’s no way to reverse the money transfer. Carvana doesn’t have any control of the banking infrastructure’s state.

To make this workflow reversible for agents, we can copy from a tried and tested system that’s used everywhere in software: Database Transactions.

In databases, a transaction lets you execute N related queries or mutations and confirm they all do the thing you expected before actually committing that transaction to the database.

In a single database, it’s fairly straightforward. In a service-oriented architecture, it’s more complicated. But patterns such as distributed transactions emerged with solutions for batching operations across multiple databases.

Carvana’s agent making decisions like transferring money and submitting orders isn’t that different from doing a distributed transaction. Ultimately, Carvana’s agent needs to read from and write to more than one data source and ensure all operations succeed before actually committing the changes.

Building transactions for agents is a long, complex endeavor, but there are some clear places we can start:

- Define the start and end criteria for transactions in agentic workflows.

- Create software that acts as an orchestrator for agentic transactions.

- Extend MCP by natively supporting transactions.

Define the start and end criteria for transactions in agentic workflows

For agents to use transactions, we need a standardized way for agents to know where the starting point of the transaction is, what criteria needs to be met to commit the transaction, and how to commit the transaction.

Create software that acts as an orchestrator for agentic transactions

SAGA orchestration is one of the methods by which distributed architectures coordinate transactions across multiple services. A centralized service orchestrates actions across the services, instructing them when to commit and rollback changes. This approach should work well for agentic transactions but there will be some agent specific challenges to overcome. Each service would need to adhere to standards (that don’t exist yet) created by the orchestrator.

Extend MCP by natively supporting transactions.

MCP tool calling is the best way to use tools between system boundaries, so any form of agent transactions necessitate extending the MCP spec. Luckily MCP has the well-established SEP process for extending the protocol. If I don’t get to writing it first, I can’t wait to see what that community comes up with!

Making decisions less consequential and more reversible for agents is the only way they will become capable of making hard decisions for us.

I can’t wait to build the solutions to these problems alongside all the talented folks in the industry. The Agentic AI Foundation recently launched and is an exciting step towards making this happen. It includes an impressive list of members, including one of Theory’s very own, LanceDB!

If you’re excited about building more capable agents, I’d love to hear from you: adam@theoryvc.com