Sell Coffee and Jeans, Not Picks and Shovels

You wake before light because the camp does. Breakfast is quick if someone drew kitchen duty; otherwise, it’s yesterday’s bread and whatever coffee you can coax from a blackened pot. You shoulder your tools and follow the creek to your claim – a rectangle of riverbank staked with twine and hope.

The day’s work is not mysterious, nor important. It’s repetitive and hard on the body. You wield your pick to break the hardpack – layers of compacted gravel and clay that water has pressed together over decades. Without the pick, you can’t reach the “pay layer” at all. When the crust fractures, you pry out cobbles and roots, then the shovel takes over. You move earth by the panful or feed a rocker or a rough-hewn sluice if your crew has built one. Shovel, dump, rinse. Let the current carry off the lighter sand and watch the riffles, hoping a few stubborn flecks settle behind them. If you’re working dry ground away from the creek, you still pick and shovel first; now you haul dirt to where you can wash it. Most of the day is moving earth. You’re thankful for the pick and shovel, but is that really the true value in the market?

The work is hard on your kit. Boots rot from standing in water. Trousers tear at the knees and pockets when you scramble over tailings or kneel to clean the sluice. Your hands crack; your back complains. For all that effort, many pans end in disappointment: a fleck if all goes well.

More and more of your take is spent in the hunt on technology. Coffee, roasted and ground before it reaches camp – no fiddling with green beans, no scorched roast of camp coffee. Denim trousers reinforced where they fail, buy you weeks you don’t spend mending. None of these things pulls gold from the river, but they make it possible to keep showing up.

For the last few years, we’ve been inundated with companies excited to be selling ‘picks and shovels’ in the Gold Rush of our time – the rise of AI. While it’s simple to make this allusion, telling folks you’re building these essential tools and relying on the listener to infer “...so we’re going to be a huge success!” A more careful reading of the history would actually inspire much caution about this label. Believe it or not, ‘picks and shovels’ weren’t great businesses!

The Gold Rush pulled hundreds of thousands into California in a few short years. Most left with less than they hoped, but a handful of names are still recognizable today due to how those habits followed the 49ers home.

James A. Folger arrived in San Francisco as a teenager and went to work at a steam-powered coffee and spice mill instead of heading to the claims. By selling coffee already roasted and ground, Folger turned a begrudged chore into a quick, strong cup before work. The product began as a practical fix for miners and became a morning ritual for households across the country. As the frontier receded, Folgers expanded east, refined quality control, and built roasting and distribution where it made sense. The brand endured because of the job it did: make mornings doable. Mr. Folger of the AI world would be hard at work building core infrastructure that bills by usage and improves over time.

Levi Strauss came west with bolts of cloth and dry goods, serving miners, railroad crews, and ranch hands who shredded pants at stress points. When a Reno tailor, Jacob Davis, began reinforcing denim with copper rivets at the pockets and fly, Strauss financed the patent and turned that idea into a product you could trust. The innovation wasn’t fashion; it was failure-proofing. Trousers that survived creek beds also survived railroad gangs and factory floors. Over time, durability became identity. Jeans slipped their origins and became a uniform that people chose even when they didn’t need them for hard labor. The generalization was the key profit vector. In the AI market, we’d expect Levi to be building vertical workflow augmentations and specialized copilots.

If you go hunting for famous picks-and-shovels brands from the Gold Rush, you won’t find names that linger in the public imagination the way Folgers or Levi’s do. The hardware houses and machinery shops that armed the diggings mostly disappeared with the camps. A few didn’t die so much as dissolve into bigger currents: Baker & Hamilton, the Sacramento “miners’ hardware” merchant, was folded into Pacific Hardware & Steel as the West professionalized; Union Iron Works, born building mining and railroad gear, pivoted to shipbuilding and was absorbed by Bethlehem Steel; Joshua Hendy Iron Works, maker of stamp mills and hydraulic giants, migrated to Sunnyvale and passed through Westinghouse on the way into Northrop’s lineage. John “Wheelbarrow Johnny” Studebaker parlayed tool money into wagons and then cars – his name survived, but the shovel story vanished behind it. The pattern is the point: there are essentially no enduring consumer name brands from the era’s literal picks-and-shovels trade; the few that lasted were absorbed into industrial conglomerates or reinvented into something else.

Panning for Gold in AI

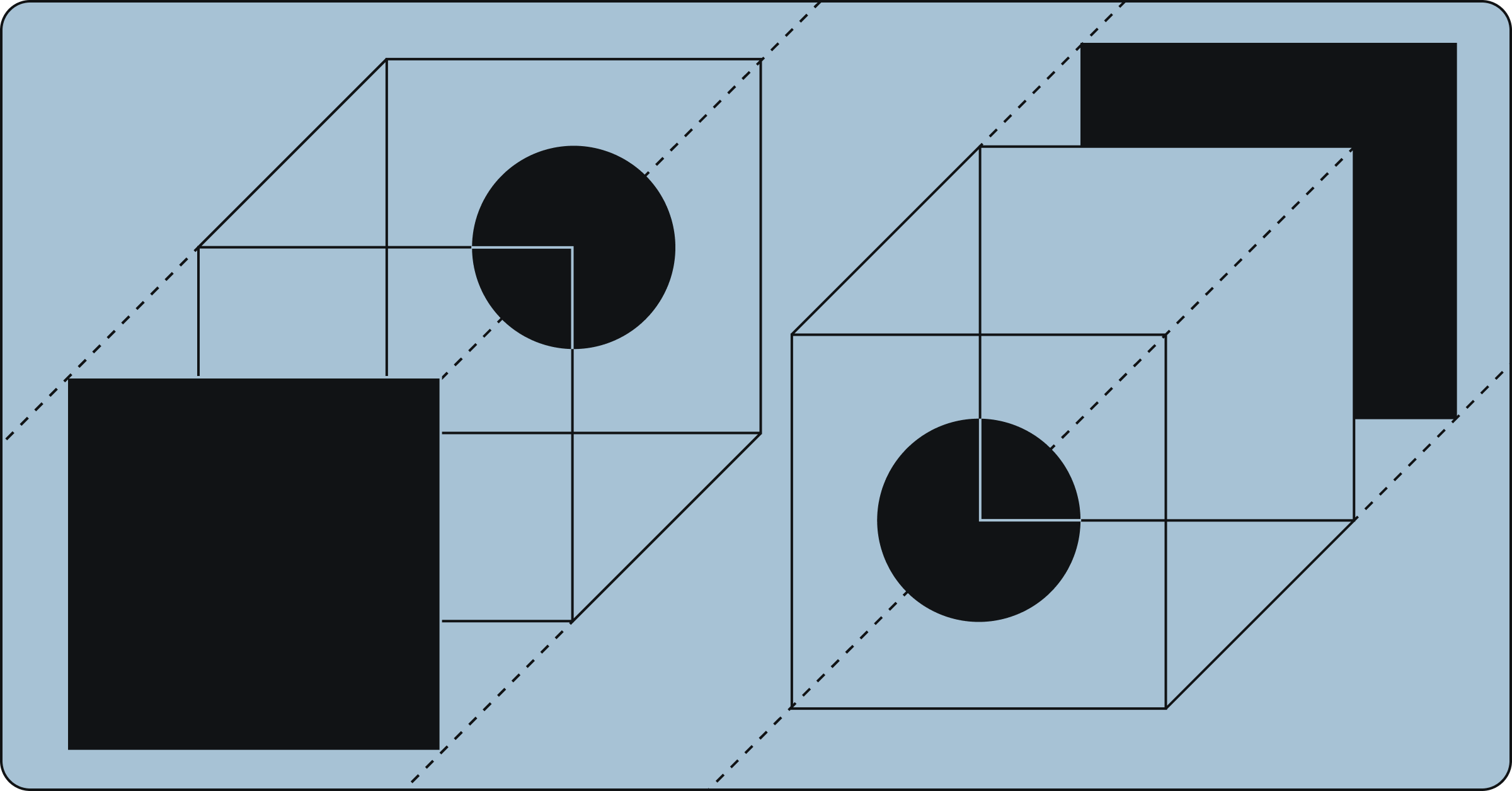

It’s a persistent trope to call the entire AI tech stack ‘picks and shovels’, dismissing much of it as ‘just a cash grab in the AI gold rush’. I think this lacks nuance – a regrettable collapse of a few different historical threads to providers and consumers. The tool makers of the gold rush can be seen today in the Ghost Towns scattered across the west, while Folgers and Levi’s remain listed on the stock exchange. So let’s give a shot at redefining these categories:

- Picks & shovels (tools/equipment): Components necessary to hunt for gold. Durable, often high-margin during a rush; demand fades or commoditizes post-rush unless you reinvent.

- Coffee (consumables): They’re not finding gold, but they seem essential despite. Metered, repeat use; strongest when embedded in daily routines; scales beyond the rush.

- Blue jeans (durable utility): Not an invention of the industry itself, but nearly essential in some form to do the job. Becomes standard apparel across contexts; defensible when it weaves deeply into how work gets done.

While all of these categories could be grouped into ‘picks and shovels’, a finer sieve helps us understand the effect of the markets for each. This elicits the question: ‘What are the coffee and jeans of the AI stack?’

Coffee is billed by usage. Your AWS, Snowflake, and OpenAI invoices probably resemble my coffee transactions (and this isn’t a reference to how much money I spend at St. Frank!). Coffee sellers can’t escape the price wars, but they can capitalize on direct line to value, and recurring revenue with good lock-in. A good sign that you’re looking at a coffee business is that if users like the product, there’s a natural way to use it more, and thus spend more money.

The AI application layer is riveting the markets because it makes existing work less arduous. It’s unintrusive, it’s exposed to your daily wear-and-tear of work. Jeans makers will start by turning pain into bearable workflows, and later generalize into more and more applications of their fabric.

Unfortunately, this leaves a lot to picks and shovels, and we’ll see how chip companies, LLMops tooling, and evals tools retrofit their factories to the next generation of products. The challenge with many of the dev tooling plays in AI is how narrow their application envelope is – tightly coupled not only to one particular kind of AI functionality, but even bound to a point in time of how we build with AI today. Things like fine-tuning platforms, AI app-builders, and Chat-with-docs builders are things that met the moment, but will require a lot of luck to outlast moments passed.